I. Feline Tendencies

There are truths which are so common to our collective lives that they cannot be doubted; truths which have been recognized for hundreds if not thousands of years.

One of the most basic rules is that, over the course of our lives, we change.

My friends and I have, over the years, discussed that while we- as people-speak of cats having nine lives, we rarely acknowledge the fact that we, as humans, do the same.

We morph, we transform, we undergo any number of variations over our lifetimes.

Some shifts are inconsequential as to be barely noticeable over the course our lives- a haircut.

And yet, some of these changes propel us into new realities which barely resemble our past lives, which bear so little resemblance to our prior existence, that we find ourselves- for all intents and purposes- living a new life.

Some of these changes are unique to the individual; some transitions involve others-i.e., marriage; while some are formally recognized by our societies and/or celebrated via ritual-obtaining a driver’s license or college degree for instance.

Some alterations are very personal, and some subtle, some require a period of time to appreciate. Some shifts involve entire societies or even the entire world concurrently.

Many of these changes are obvious- the student, for instance, who finds himself drafted into a military conflict. One minute he or she is living a carefree student’s life and the next month, he’s walking through the jungle with a rifle hoping to kill others before he’s killed.

None of this is standardized, none of these changes are guaranteed or written in stone. Nevertheless, these changes are true and all of us, to some degree, will experience this reality multiple times during our lives.

How many lives we live in one lifetime is, of course, an opaque and arguable matter even to the person living that life. Where one life ends and the next begins, is a matter of observation, opinion and debate.

Did the birth of each of my sons constitute the start of a new life, or did I shift into my next life- called parenthood with the birth of my first son- a life which continued with the birth of each subsequent son?

Some changes are not so personal. Across the globe, many of us find ourselves living a very different life post pandemic. Millions of us, perhaps have simultaneously and collectively morphed into new lives.

The fact that we are beings of change is so beyond cavil, beyond doubt, that this truth is etched into our lives, our beliefs, our art, our religions.

The Buddha said that change is the only truth. In the Nakhasikha Sutta: it is said:

At Savatthi. Sitting to one side, a monk said to the Blessed One, “Lord, is there any form that is constant, lasting, eternal, not subject to change, that will stay just as it is as long as eternity?”

The Buddha responded, “No, monk, there is no form… no feeling… no perception… there are no fabrications… there is no consciousness that is constant, lasting, eternal, not subject to change, that will stay just as it is as long as eternity.”

Christians celebrate the transubstantiation, celebrating man’s collective ability to change, to transform, to merge with God, on even a molecular level: “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me and I in him” (Jn 6:56). In being united to the humanity of Christ, we are at the same time united to his divinity. Our mortal and corruptible natures are transformed by being joined to this source of life.

On a lighter level, the British television show, Dr. Who, has made hay for over a half century with this trope, completely changing the appearance and personality- while maintaining the existence- of the lead character countless times.

Thus, for all of us, change is constant and inevitable-examine your own life and appreciate this truth.

Now contemplate a step further: what if you are suddenly so completely ripped from the world in which you comfortably exist and are propelled into a new reality, so different from your last, that you cannot appreciate, cannot comprehend, that you have made this metamorphose?

One day you wake up and you don’t know who you are, you don’t recognize the world around you.

Now what if millions of people, all over the world, in a short time span, concurrently underwent similar change?

Such changes are not without precedent. There is a medical condition whereby those inflicted are so ill- their ability to perceive themselves and the universe in which they live is so completely impaired- that those afflicted cannot perceive that they are ill; rather, they believe themselves, wholeheartedly, to be well.

This condition, anosognosia, can be understood to mean a “‘lack of insight’ or “lack of awareness.”

It is estimated that anasognosia affects approximately 50% of individuals with schizophrenia and 40% of individuals with bipolar disorder—and is believed to be the single largest reason why individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder do not take their medications (because they don’t believe themselves to be ill, they see no need for medication).

In short, those afflicted cannot, for physiological reasons, understand that they are sick. As a result, they often refuse treatment which places these patients at greater risk for any number of problems including homelessness and being subject to arrest and violence.

II. Vanceburg to Tucumcari

I’m staying, in September 2022, with two of my oldest friends Dave and Amy. I’m in the middle of a long trip.

I also stayed with them last year when I made a similar cross-country trip. Despite their hospitality, last year’s trip was retched. I can’t identify the reason(s) for the feeling of torpor, malaise and unhappiness which had hung over the entire last trip. Everywhere I went was horrible; everywhere I went I was miserable.

Was it me or the world or some combination of the two?

This year’s trip has been much better, all the way around.

When I compare the two trips though, I’m struggling to determine what made last year’s journey such a horrid trip and this one a pleasure. I can point to specific instances, but, taken as a whole, I have no idea of why I, and damn near everyone else I met last year, seemed so miserable.

In the month before I started last year’s cross-country expedition, I took a long weekend trip through Kentucky-along the Ohio River- a shake down trip to work out the bugs before departing on my longer cross-country trip.

This was at the tail end- or what we all were hoping was the tail end- of covid, in the fall 2021.

On this Kentucky trip, I hit a number of river towns- and in particular Augusta, Maysville and Vanceburg in an effort to prepare for my longer upcoming trip and to also triangulate the mood of America at that difficult time.

I knew that things had changed- in some cases, drastically- since we all collectively entered hibernation, so I took this preliminary excursion because I wanted to see where we were as a country.

What I could not have known was just how much America had changed in the prior year and a half.

I had worked from home each day during covid and had largely avoided the outside world.

So I went out into the world, and during that time in Kentucky I found precious little to explore, precious few people with whom to interact.

What I found on both the short Kentucky trip and my subsequent travel out West in 2021, was that America was an unhappy place and that it was broken in many fundamental ways

I found most places, most people, to be quite empty and stressed; sad and vacant.

Some places like Vanceburg were desolate. In driving through that gray town, in the middle of the day, I saw no one, save for a few Sherriff’s deputies in front of the courthouse. I walked about and found nothing. I tried to chat up the deputies and got nothing for my efforts, save cold, short, perfunctory replies.

The remainder of the town was literally empty. It was a small town- a half dozen or so blocks- a minor stop on the Cardinal Amtrak route- which sat on the banks of the broad muddy Ohio. Almost every single store was empty, their storefronts vacant.

I felt as though I was walking through the set of an old Twilight Zone episode, a post-apocalyptic landscape, a Hopper painting.

Augusta- a small tourist town (they-along with nearby Maysville claim to be the birthplace/childhood home of George Clooney) forty miles east of Vanceburg was not so quiet. Yet while there were a number of geriatric tourists, everyone seemed somewhere between unhappy and confused. There were a few restaurants, a bar open, but there was no feeling of life, of spontaneity.

Maysville was much the same.

My trip out west, shortly thereafter, was different but not any better. There were many places which were crowded, though the people I met were equally vague.

I wrote at the time:

It is a fairly straight and level shot across the windy empty panhandle of Texas. I made my way into New Mexico and eventually to Tucumcari, barely noticing that I had traded the Texas desert for New Mexican desert.

Pulling down the main street of Tucumcari I am literally stunned.

I’d been here some 8 years before and had found the town then to be on the verge of hard times. Yet, Tucumcari today looks closer to Hiroshima after the bomb than an American town. The majority of businesses are shuttered and some are literally overgrown.

There are countless empty restaurants and other businesses. Most of the hotels and motels are closed as well. The main strip which for decades has been full of retro motels (Tucumcari sits astride the famed Route 66) and has, for decades, served as a meeting ground for America’s classic car crazed boomer crowd looking to get their route 66 kicks.

Today, however, Tucumcari-population 5,000 (almost)- looks like Warren or Youngstown Ohio in its worst rustbelt days. The town is an empty desiccated cicada shell of humanity. The webpage for the chamber of commerce site advises hopefully: Tucumcari’s thriving community is bold, innovative and knows that by working together we all have an opportunity at success. Get to know how our chamber works for you. The link leading to the Chamber’s visions of success page is broken.

I found my way to the hotel I had previously booked online. I swore I knew the gentleman behind the desk. Sure enough, when I give him my name he is quick to tell me that I stayed in this very same motel, the TriStar, in 2013. I had, in fact, stayed in room 105 at that time. He regrets that he cannot offer me the same room at this time but is happy to offer me room 107.

Having collected my driver’s license and credit card, he proceeds to charge me $7.26 for taxes. I already paid for the room and was quite certain paid for any additional taxes as well, but given the sorry nature of the town, I let it slide. Tucumcari apparently needed the $7.00 more than I did.

I ask about places for dinner he tells me that in the entire town, there are three restaurants open and he’s not certain that any of them are open on Sunday evening. He shares with me the location of the three restaurants and wishes me luck.

I head back out on the strip and find the first closed, and the owner of the second restaurant is shutting the front doors as I walk up. He tells me to try the Pow Wow Lounge up the street and that they should be serving.

I eventually make my way to the Pow Wow after hitting the only grocery store in town to pick up a few provisions in case I’m not able to get dinner out.

The grocery store inside is crowded with locals. Here there is, at least, a genuine happy demeanor in the air. A father who appears to be a rancher or farmer stands in the checkout line in front of me, with his seven children, chatting up the cashier who turns out to be the mother of the children. She lets the children go with a kiss and stern warning to clean their rooms.

In time, I find the Pow Wow Lounge and Restaurant where I see that literally every car in town and the few tourists staying here tonight, are in fact attempting to simultaneously dine there.

To complicate matters there’s precious little parking, but two entrances to the same dining room with people forming expectant groups in each entrance. Everyone is clearly waiting impatiently to be seated in the already full restaurant. It is, in short, a clusterfuck.

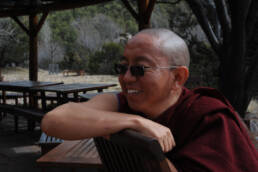

I do my best to be patient as the manager, who appears to be a native American of about 60 with short cropped gray hair and beard, does his best to juggle the incoming crowds.

Eventually he offers me a seat at the bar where I’m waited on by Brenda, a middle age bartender who is kind- as is all the other help in the place- even though they are clearly overwhelmed and working their asses off.

I begin to wonder if it’s going to be possible to even get served in this place given the madness inside. The people working inside are, however, not only attending to their tasks in a cheerful manner; but are making a legitimate effort to do their very best. I decide to have a little patience, a little faith.

Apparently, the people in the kitchen are also working their asses off because in a reasonable amount of time, Brenda brings me a chicken sandwich covered with hatch chiles, cheese, tomatoes, pickles and lettuce with a guacamole mayo slathered atop the entire mess. There also a very healthy side of sweet potato French fries. All in all, it’s as good a dinner as one can hope for in Tucumcari, or Chernobyl, after the war.

I tip Brenda 25% and head out to photograph what’s left of the town’s art deco architecture and the neon lights which made Tucumcari- at one time- relatively famous.

As I work- walking up and down main street- night falls on the desert. I think what would it be like to live here? The tourist jammed inside the Pow Wow Lounge are all clearly headed elsewhere, but what would it be like to live here- to be trapped here?

It’s clear that damn few of the people passing through are here stay, to explore, let alone vacation here. If people did stay, the town wouldn’t be nearly a ghost town. Why I wondered was Tucumcari dying? It was, clearly at one point, a prosperous town- a hub of the route 66 movement- what changed?

What would it be like to get up every day and work so hard for a group of people who barely notice you, barely notice your town, who only want to be fed and offered a place to sleep; who only want to leave your town as soon as humanly possible.

What would it be like to wake up every day after working so hard all night to only be rewarded by spending another day in a dying town with damn near nothing offered in return?

I photograph the few remaining neon lit retro motels lining route 66 and then make my way back to the TriStar to my entirely mediocre motel room which is, at the end of the day, just fine and everything I need 1500 miles away from home: specifically, a roof over my head for 8 hours.

One could do much worse.

Poor Tucumcari. Morning.

If anything, this sorry town looks worse in the daylight. From what I can see, there’s little more than a clutch of very good people adrift in a leaking rowboat of tourism, adrift in an ocean of American economic inequity.

As one writer aptly and recently noted: Today, “Tucumcari feels like a lived-in ghost town. Abandoned icons, like the Ranch House Cafe and the Westerner Drive-Inn, share the scenery with restored gems, like the Blue Swallow Motel and La Cita Mexican Restaurant.”

As I leave town, I will take with me a vision I saw driving into town. Driving into town, I came upon the young man and women on a motorcycle. He’s pulled up to an intersection and is waiting for the light. He looks fine- a good looking young kid, going through his day. However, on the back this bike was a young dark-haired girl who looked crestfallen, crushed, and absolutely broken hearted.

There could have been, of course, any number of reasons for her chagrined look, but I couldn’t help wondering- reflexively, whether her appearance wasn’t secondary to living in, what must be, one of the saddest towns in America.

There’s obviously no way to know for certain, but her sadness, no matter the cause, is certainly an apt metaphor for this gloomy town.

As I leave Tucumcari, I note that there’s a whole section of town, accessed by the last highway exit, which is not only desolate, but which consists of heavily vandalized empty commercial shells- many of which have been burned to the ground. This end of town is a literal war zone.

It’s one of the sadder sights I’ve ever seen in America.

III. Funking Hard

Shift focus. A year later, ensconced in Dave and Amy’s happy, safe, clean and bright Albuquerque adobe, last year’s entire trip floats through my brain, more of a fog shrouded memory rather than a linear or coherent mental film.

A year later, I’m doing better and America is doing better, but still a fucking mess.

I think back.

During covid, even on the best days, I found it impossible to create and I could not say why.

I was miserable, but could not, to any real extent- explain why. Obviously, there was the plague, but I had been lucky. Me and mine were healthy and I had worked nonstop since the start of covid. In fact, I still had my cognitive abilities. I was excelling in a job that was entirely new to me, one in which I had no prior experience.

Purely by circumstance I found myself working for a large corporation helping to supervise, from my home office, 80 hearing officers across the country. Circumstances dictated also that for many days I had to run the entire project on my own.

I had no past experience doing anything like this and I, as a very general rule, loathed corporations. I wanted nothing to do with working for them. None the less, I excelled at this job and was rewarded with multiple substantial raises, and serious benefits, and was also permitted to take a month-long sabbatical after a year.

I stayed and worked hard every day with good people. There really wasn’t anything else to do. And so, things went largely well during the day. I made bank during the day, and at the end of the day I walked down the hall and I made dinner for my beloved and our sons. It was not a bad life. The time I spent with my family was happy.

It was not however, a happy life outside of work and family.

I struggled mightily, outside of work. I created nothing. I shot nothing, I’d been a writer and photographer for a long time and spent pretty much any free time I had engaged in those activities. Photography and writing meant a great deal to me.

And yet, Covid killed everything, or seemed to.

In terms of photography, I had, over the last twenty years, been very much involved in travel and music photography. Both literally died during Covid. There were no concerts, one could not travel.

I wrote very damn little. The energy I had at work, dissipated outside of work, I felt as empty and soulless as Vanceburg Kentucky- why?

Why outside of work- and even when I was on the road did I end up floating about- like a zombie looking for a sense of self?

And why was so much of the world, acting in a similar manner?

I did not see people; I did not hear from people.

Before the plague, I had many friends. My social calendar was always full.

Now? Radio Silence, nada, nothing zilch.

Damn near everyone I knew seemed empty.

For reasons which I couldn’t quite put my finger on, I thought that the answers to these questions weren’t going to come from within but from without.

Was that right? A fair assumption? I had searched outward for answers as well as inside my heart and soul and had not, to date, found many answers anywhere.

It was hard for me to feel much of anything as I drove from one empty Kentucky burg to another, another ghost simply looking for similarly situated lost souls in Central Kentucky and/or dinner on Sunday night in Tucumcari.

There were some random clues which didn’t seem to add up to anything.

I kept searching, spending a weekend alone in the woods, in a cabin by myself (in retrospect, a stupid idea- one cannot cure emptiness and ennui by isolating oneself).

But I got nowhere.

I could see that damn near all of us-myself included- were off our game, but I could not find a cure.

Everywhere I went- the grocery store, at home, the road-people seemed listless and lost. I couldn’t decide if I was imagining this in my head, or whether the entire world had lost its mind.

Then, recently, I read a piece on a site created by a touring musician. In this piece, he recounts how he met a women on the train and they began to chat.

She inquired as to what he did and he explained that he was a touring musician. As part of this conversation, he explained how it was difficult to get back into the touring business given the myriad of problems facing musicians at present including the number of no shows ghosting each show.

I explained about my work in music, and the problems of touring during the pandemic. …. And I mentioned the issue of “no-shows.”

No-shows are people who buy tickets to an event, but don’t go. You might think this only happens rarely, and pre-COVID you would be right – the normal rate of no-shows to music events was less than 5%. But recently, the statistics have been shocking: up to 50% no-shows in 2021, according to testimony from a representative of the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) to Congress. And this hasn’t gone away in 2022 – no-shows have now become a serious issue for venues of every size, in a way they never had been before. “Even for largely sold-out tours like Pavement, the no-show rate has spiked,” reported Billboard last week.

Could this be right? Such a phenomenon made sense to me on a personal level. I was finding it hard to be interested in anything- to go out and do anything. I knew other photographers, like myself, who had little to no interest in shooting concerts, hell, who had little to no interest in photographing anything.

I ran this idea of no shows past a couple friends who were musicians and while they did have any hard statistics, they confirmed that no shows were a real problem.

No shows also created a snowball effect for other folk. Not only for musicians, but for club owners who can’t sell beer to people who don’t show up. Those no shows also did not buy merchandise; and it’s merch money that keeps a touring band in gas and cheeseburgers.

There were similar reports of apathy and ennui on a larger scale. I read a piece from a life coach wrote about what she termed Post Covid Apathy:

The events of the past couple of years have been traumatic for many of us. From a global pandemic to social and political unrest to economic recession, we’ve been faced with challenges that can take a toll on our mental and emotional well-being. And for some people, these challenges have led to a loss of motivation. If you’re struggling to find the drive to do your work, you’re not alone.

So what if no shows applied not just to touring bands, but also applied across countless forms of entertainment, work and, perhaps all forms of life.

What if we were all stuck?

Tresetta Washington BSW who authored the aforementioned work on post covid trauma explains:

When we experience trauma, our brain goes into survival mode. This “flight or fight” response is meant to protect us from harm, but it also has the effect of shutting down non-essential functions like decision-making and goal-setting. As a result, we can find it difficult to motivate ourselves to do things that don’t feel immediately essential to our survival.

Yes. Yes, Yes. Now I felt as though I was wading from the swamp onto at least semi firm ground.

For this was a topic I knew not just something, but a lot about.

You see, one upon a time, I was a trial lawyer for about twenty years. I was very good at my job but came to hate it with a white-hot passion.

I fell into typical trial lawyer syndrome. Too many drugs, too much alcohol. I was depressed and things at home were lousy. And I might have been just a tad motherfucking angry all the motherfucking time. I broke nearly all my molars from grinding my teeth in my sleep. My beloved and I divorced.

Flash forward, I attended a continuing legal education seminal. The chief justice of the Kentucky Supreme Court explained that because the suicide rate for Kentucky lawyers was six times the national average, (lawyers, as a whole, have the fourth highest rate of suicide by profession) she was going to explain to us what was going on in our brains and she asked that we examine our lives to determine if what she was explaining applied to any of us.

She explained that in a stressful situation — whether something environmental, such as a looming work deadline, or psychological, such as persistent worry about losing a job- or dying from a pandemic — can trigger a cascade of stress hormones that produce well-orchestrated physiological changes.

Chronic stress that never or rarely abated- generated by things like 2000 unhappy or desperate phone calls a day- could turn occasional flight or flight symptoms into a never-ending process whereby chronic stress introduces constant high cortisol and adrenaline levels into your system. This can disrupt basic processes throughout your body and increase your risk of health problems, including heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Chronic stress is known to contribute to: Depression and anxiety.

I knew the words were true as soon as I heard them spoken and that day marked the beginning of the end of my legal career

Ten years went my- and by and large I got a handle on my life. I quit law. I got back together with my beloved and repaired by relationship with my sons. I pursued art in a major way and traveled. It was a long difficult slog, but I, we, created a worthwhile life.

And things were good for a long time until covid and my old friends cortisol, adrenaline and stress reared their ugly heads again.

Could it be so? Could the struggles of the last two years simply be the same old fight in a new package?

Could this be true for many of us- were we suffering collective chronic stress making us zombies? And if so, then where do we go from here? How do we cure ourselves?

Research suggests that it’s too early to engage in wide-spread generalities, but research also shows that many, many people have and/or are suffering significant mental distress as a result of covid and/or treatment for same.

The Mayo Clinic for example says people with severe symptoms of COVID-19 often need to be treated in a hospital intensive care unit. This can result in extreme weakness and post-traumatic stress disorder, a mental health condition triggered by a terrifying event.

Up to one-third of people who experience the sensation of not being able to breathe, as in severe cases of COVID-19, develop clinical PTSD after those experiences.

In short, as with other cases of prolonged trauma, it appears entirely possible-additional research suggests– that an exaggerated stress response to covid may perpetuate cortisol dysfunction, widespread inflammation, and pain.

At the very least, it was clear that things had changed for the worse, and I needed to learn why.

And, most importantly, I needed to know how to move forward.

IV. No input no output

It’s a stupid beautiful day in Albuquerque. Brilliant blue skies, warm temps. Which is to say it’s just another day in the neighborhood.

Things have been better since I arrived here.

I’ve seen the local sites- which are cool- ABQ is a very different kind of town. It has a young energetic population. It’s diverse.

And talking with Dave and Amy definitely raises my spirits. Each night we’ve gone out- and either picked up dinner to go from a local shop and carried it to one of the many nearby local breweries and drank and ate there; or bought carry-out to take back to their place.

The breweries are invariably crowded, people speak excitedly, there/s a buzz in the air. And dogs, there are dogs everywhere, including at many of the brewpubs. Several times we bring Annie and Louis -Dave and Amy’s two lovely Aussies.

I’m feeling better all the way around and decide to stick around a few extra days, thinking that in this atmosphere, my heart and soul might catch fire.

Dave’s- who has played music his entire life- has found a band in ABQ. I’m also staying an extra couple of days to hear him in his first gig with this new band.

Wednesday morning. Dave has pedaled off to work and Amy is working in her home office. I’m poking around planning a day.

On the breakfast bar, where we have coffee and breakfast each morning, I see that Dave has picked up some new music.

It’s a new collection of old work from Joe Strummer- the former singer and guitar player for the Clash. Dave and I share a love of the Clash.

After the Clash, Strummer formed a new band called the Mescaleros. Their story is told in a film called the Let’s Rock Again by director Dick Rude.

The film is fascinating for a number of reasons. One of the primary reasons it’s interesting is that after the Clash- which had made Strummer a world-wide star- Strummer did nothing to little musically for a very long time. He basically sat out the 90’s.

By the time he came back and formed the Mescaleros and began making music with them, the world had moved on- relatively, Strummer was no one. The film details his journey back from obscurity.

There’s a stellar scene in the movie in which Strummer is literally sitting on the boardwalk in Atlantic city, handwriting notes advertising the Mescalero’s show for that evening. He stands with his bandmates handing these notes to people walking along the boardwalk.

He could have been any high school kid from nowhere trying to lure people to his band’s first gig.

All of this is magical, because the film and the music that Strummer made with the Mezcaleros contains not an ounce of woe. Strummer does not mourn his precipitous fall from fame. Rather, he and his bandmates are happy and determined to be heard.

Strummer says his only goal is to sell enough records to break even, because meeting this goal means that he can record again. He just wants to keep the wheel spinning.

The film is one of the most inspirational things I’ve ever seen. The Mescalero’s work, Streetcore, is lovely.

In any event, the new collection sitting on David and Amy’s breakfast bar that morning is open and I can see, it contains copious liner notes.

I began scanning the liner notes. I was casually reading when my eyes fell across the following words, “No input, no output.” I read just those words and a key turned in the lock of my mind.

It seems an obvious and even trite observation, but those words made me realize that for the better part of a year and a half, I’d had no input. I realized that because I had no worthwhile input save bad television and grim silence and the joy of creating spreadsheets for 40 hours a week, that I had grown empty.

Covid had made me, made America, as a whole, for the better part of a year and a half- a sterile place devoid of interest- of input. We had all collectively been living like spiritual, intellectual and emotional zombies. We had been living with a severe case of collective social anasognosia.

We didn’t realize that whether or not we had suffered from Covid, that we were sick- that our minds had been anesthetized. And because we did not appreciate the severity and nature of our illness, we did not know how to cure it, we didn’t know how to make ourselves better.

And so, we had, I had, been stumbling from place to place- sometimes at 80 miles an hour, looking for something to make me feel, well, anything.

I was lost- we were lost- and it didn’t matter whether we had been locked in our home offices for a couple of years and/or drifting about the vacant city or empty countryside.

V. Redemption Song

And so the questions becomes, once we realize our illness, how do we get better?

My idea is that we begin by mourning what we have lost.

Everyone lost something because of Covid- some much more than others.

I lost a couple of avocations that made my heart beat, that drug me out of the house a good 100 nights a year- that put me in proximity of countless creative souls.

And so we need to mourn what we’ve lost. The people we don’t see anymore and the joy which these people brought to our lives. You can’t get that joy back, though if you’re lucky you can get back images of that joy.

One of the things about being a digital photographer- especially if you’re older and didn’t grow up with tech, is that it’s so easy to lose track of your work literally. You wake up one morning and your work isn’t on your hard drive. You back up, of course, but reinstalling multiple collections can be a stupendous headache that leads to more lost photos.

All of which is to stay that it’s not an unheard of phenomenon that 70,000 photos-which disappeared from my computer several years ago- showed up on my heard drive one morning.

I spent a week recently going through them and crudely trying to organize them.

There were countless photos of places I had visited, shot and could barely recall. There were photos of hundreds of gigs. Cross country train trips. Weeks spent in cities and beautiful empty country alike. It was mind boggling to me how many places I’d been, the people I met, the shows I shot.

There were photos of trips to Navajo and Hopi Country, countless trips to New Orleans. Montreal, San Francisco.

I won an arts grant which resulted in my traveling the country by train for six continuous weeks. On that trip, I crossed the country five times. Several years later I took my sons on a three week train trip circumambulating the country.

These trips led to important friendships. New Mexico became an adopted home. I practiced Zen in a beautiful monastery in Santa Fe and shot the countryside in Taos, as well as the mountains beyond. I got to know stretches of the San Juan and Sangre de Christos mountains by heart.

I realized that before covid I had lived a very fortunate life of constant motion, collaboration and, on the best days, joy.

When covid came, it was like hitting a brick wall, in a small fragile sports car, at 120 MPH.

How can I get that life back, I wondered?

I spent a long time brooding over this question, scowling over the basic unfairness of the circumstances, wondering how much energy I could muster up to do it all again at sixty.

And then I grew up and realized that what we’ve, I’ve, been through, is nothing new.

The truth is that we need to appreciate that the idea that we knew the contours of our lives before covid- that we knew the shape of our journey pre-covid- that we knew where were headed- is/was an illusion anyway.

We were always making up our lives as we went along- whether we wanted to admit it or not

Some of us made a show of living neat organized lives, of pretending we knew where we were headed.

We knew we were going to university and then to grad school, moving to a coast and marrying a perfect spouse.

Some of us were much more honest about the fact that we were making things up as we went along.

No matter where we fell on this spectrum, it was all an illusion. No plan, no dream is ever guaranteed. we’ve always lost people and bits and pieces of our dreams before covid.

Things before and after covid never went as planned, for better or worse.

In short, things get fucked up and this has always been the truth.

One night there’s a tornado that levels your beautiful home. You can’t get into the grad school you wanted. Biology bores the piss out of you.

Covid fucked up many lives and many plans, but it’s not game over. It turns out that covid is just one more spanner in the machinery of your life. And it won’t be the last.

We need to appreciate that while we are now on a different journey- courtesy of covid- that this new journey is, after all, just one more different journey.

This shit happens all the time.

As Clay Shirky in his essay Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable, in which he examined Elizabeth Eisenstein’s magisterial treatment of Gutenberg’s invention in her work The Printing Press as an Agent of Change; as well as the demise of the daily print newspaper, wrote:

History and progress are a series of great tsunamis. The real changes in history are brought about by cataclysmic events and inventions. These events and inventions have a way of clearing the landscaping, wiping out the current technology and present systems.

Historians, for goods reason, Shirky points out, tend to concentrate on these critical moments- that is: the event and the immediate aftermath of the event and or invention.

Mostly, these events mean change.

And as humans we don’t like change- either on a large or small scale. This was/is true both at the time of the Guttenberg press, and the demise of the daily print newspaper and it’s equally true concerning the changes wrought by covid.

As Shirkey wrote:

And so it is today. When someone demands to know how we are going to replace newspapers, they are really demanding to be told that we are not living through a revolution. They are demanding to be told that old systems won’t break before new systems are in place. They are demanding to be told that ancient social bargains aren’t in peril, that core institutions will be spared, that new methods of spreading information will improve previous practice rather than upending it. They are demanding to be lied to.

To summarize: (and to paraphrase) the great composer Warren Zevon, “our shit’s fucked up,” and we don’t like it.

Such Tsumani’s are painful, Shirky correctly writes, because while “these huge moments in history are often swift, as is the destruction that they bring to the status quo, the rebuilding from these events is often slow and haphazard and uncertain.”

And we don’t like slow haphazard and uncertain. We want the diner up the street to make meatloaf every goddamn Tuesday. Shirkey, “this is what real revolutions are like. The old stuff gets broken faster than the new stuff is put in its place.”

The tsunami which was/is Covid has seriously altered lives and processes and many of us do not wish to admit this, to deal with the aftermath, the slow messy rebuilding process.

But for those, like myself, who have limited time left to follow their dreams, we must start on a new dream, a new journey-no matter how inconvenient that change may be.

Even if it means living a half dozen or a dozen false starts. Even if it means that we have to go to Vanceburg and Tucumcari before finding our way to Albuquerque and Dave and Amy and then home.

We need to embrace the reality that we were never going to get the journey we wanted anyway- no matter how intense our hopes and dreams.

All we can do is walk the path before us; we can only appreciate the new path we are on; we can only get on with Plan B.

We need to lose the denial and the philosophical blatherings which leave us wandering in circles in downtown Pulaski Oklahoma.

We don’t have to like the tsunamis and catastrophes and pandemics in our lives, but ultimately, if we’re going to have any kind of life worth living, we need to go forward.

Once upon a time the great writer and naturalist and Zen Master Peter Matthiessen walked over the Himalayan mountains with naturalist George Schaller. He joined Schaller’s trip (an expedition to study wild blue sheep in the region) seeking solace and clarity after the death of his wife from cancer.

Matthiessen thinks he will find some sort or insight, of relief, through this trip, if only he can find the rare and elusive snow leopard in its natural habitat.

Matthiessen- who began studying Buddhism after his wife began practicing- has been, at this point, studying Zen for decades. Given his spiritual practice, Matthiessen also wishes to visit a remote Tibetan Buddhist monastery in the region.

He hikes for weeks over and through the snow filled Himalayans and in the end, Matthiessen does not see a single snow leopard; though at the end of his trip and after much tribulation, he reaches the monastery- The Crystal Monastery- and once there meets the head of that monastery (the Lama) who is so physically disabled that he cannot walk.

Matthiessen finds the Lama sitting on the cold stone floor of his remote monastery, swaddled in a wolfskin robe- his legs useless.

The following scene takes place

The Lama of the Crystal Monastery appears to be a very happy man, and yet I wonder how he feels about this isolation in the silences of Tsakang which he has not left in eight years now and because he is crippled may never leave again.

Since Jang-bu seems uncomfortable with the Lama or with himself or perhaps with us, I tell him not to inquire on this point if it seems to him impertinent, but after a minute Jang-bu does so. And this holy man of great directness and simplicity, big white teeth shining, laughs out loud in an infectious way at Jang-bu’s question. Indicating his twisted legs without a trace of self-pity or bitterness- they belong to us all- he casts his arms wide to the sky and the snow mountains, the high sun and the dancing sheep, and cries: “Of course I am happy here! It’s wonderful especially when I have no choice.”

In his wholehearted acceptance of what is, this is just what Soen-roshi (Matthiessen’s Zen teacher) might have said: I feel as though he had struck me in the chest. I thank him, bow, go softly down the mountain.

Butter tea and wind pictures, the Crystal Mountain, and blue sheep dancing on the snow-it’s quite enough!

Have you seen the snow leopard?

No! Isn’t that wonderful?

Matthiessen comes to realize- in true Zen master fashion- that it does not matter if he sees a snow leopard. He’s walked hundreds of miles, and endured substantial hardship, to not realize his hopes, his aspirations.

What is important is acceptance of the path before him, even if that path is not the original path of his dreams. Wholehearted acceptance of what is now.

In the end, Matthiessen embraces that new reality. He makes a life of the journey before him.

I have for years told people that life has taught me that you become an adult when you realize that there are times in life in which you must accept that things do not have to get better, that sometimes there is no floor, only a free fall.

You think that you are on one path, but sometimes, inexplicably, you find yourself ripped from your expectations.

And so life goes.

You can either get up and walk the new path or live a lie

VI. New Path

Of course, walking a new path is not a simple or immediate process.

We buy tickets to shows and we never use them, instead we stay home another night binging Netflix’s.

We learn that surrendering to inertia is easy- and that while it is not anything near a rich full life, the couch and television and booze help to numb the pain we suffer after losing our dreams.

And this is a long and slow and confusing process. We don’t know what we want because, how in the world could we know under the circumstances?

But here’s the most important thing: we do need to go forward.

We also need to realize that this new path does not have to be one of despair and hopelessness- it can lead to new places and it can offer us not only solace, but happiness in new unanticipated ways.

This new path can lead us to good places- we just have to be willing to make the journey.

We have to get up and go to the show. We have to get up and make the painting, we have to get up and load the car and head out on the open road and look for new places and new people and chose to live the rest of our lives to the best of our ability.

The truth is that inspiration awaits us just down the path. We simply need to make an effort to find it. To walk forward with open eyes and an open mind.

I found on the bookshelf in my den the other day, a book that I’ve owned for a long time but have not read in years. It is a slim volume containing writing by the great Spanish Poet Federico Garcia Lorca.

I came across the following paragraph in the introduction:

In writing about Lorca’s foray into what he calls Poetic Fiction, Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno writes in the introduction that:

The opening legend, “Santa Lucia and Santa Lazaro,” written in 1927, the longest and most sustained of the tales, was likely inspired by Salvador Dali’s prose poem “San Sebastian.” According to Ian Gibson, Lorca’s biographer, Dali’s work completely overwhelmed Lorca, and opened a major new direction in his own work, namely that of allowing the unconscious to provide the inspiration for a poetic narrative… Barbarous Nights p.2

Let’s unload this paragraph- what is happening?

What is happening is that Lorca picked up a work by Dali – an artist he greatly admired. He found Dali’s work not only powerful, but so moving that it generated not only a new piece of his own work, but it also also propelled Lorca to a new vision of his art as a whole.

Dali inspired Lorca’s work, who has in turn, inspired countless others. This is a creative chain which will continue to be forged, no doubt, through centuries. Even after Lorca was executed by the Fascists at 38.

No voyage, literal or creative, is a simple straight excursion.

Rather, we stop and start and are thwarted and forced to begin anew, time and again, and that is what we do. Some days obstructions are monstrous, seemingly affecting the entire world, but we carry on, because our only other option is bitterness and sterility. We spend the rest of our short unhappy life mourning what we think we have lost instead of living plan B.

Contemplate the options, the paths before you. Consider which path is most likely to lead you towards happiness.

Head out in that direction.