Pierre Dufour is fiftyish, fit, silver-haired, amiable, and gracious. He dresses well and speaks with a heavy French accent befitting his roots in Montreal. For sixteen years, Dufour was the director of Opéra de Montréal.

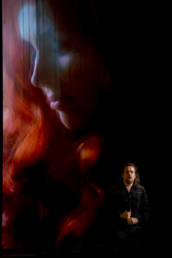

Roger Waters was born and raised in Surrey, England. His looks belie his seventy-four years. He is, like Dufour, well spoken, intelligent, and gracious. For many years, Waters made his living in music as the bassist, songwriter, and vocalist for the enormously successful band Pink Floyd, which recorded some of rock’s greatest albums, including The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975), and The Wall (1979).

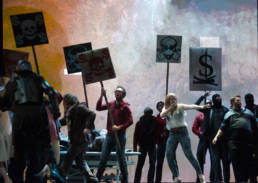

Together, Dufour and Waters are the creators behind Cincinnati Opera’s latest/current production, Another Brick in the Wall, based on The Wall. In the album, Waters is Pink, the autobiographical antihero played in the Cincinnati Opera premier by baritone Nathan Keoughan.

The album begins with Pink suffering a breakdown after spitting on a fan during a concert. He collapses, is hospitalized, and is haunted by memories of his father’s death.

A father’s death is a commonality Dufour and Waters share. Both lost their father at any early age and have been suffering that loss throughout their lives. Says Dufour, who lost his father when he was eight, “I’m fifty-five right now, and I don’t want to say it’s a quest, but this is something that you carry…all your life.”

Waters’s father died while flying a mission over Anzio, Italy, during World War II, just three weeks after enlisting. Waters was just five months old at the time. The Wall is, in large part, his attempt to explore the issues surrounding that loss.

For Dufour, the opera began one fall day when he was still quite young and living in his parent’s home. He dropped the needle on The Wall and, as he still clearly recalls while sitting in the conference room of the Cincinnati Opera decades later, he “fell in love.”

The recording, says Dufour, “is 127 minutes long. Whenever I could listen to the album, I knew I had that time. If I could not listen to the entire record at once, I would always pick up where I left off. What hooked me was the quest of the father.”

For Dufour, The Wall is not a collection of disparate tunes; it is a single unified work. He has heard The Wall as an opera from the start. At some point he began to dream about making it into a true opera. While working as the Director of Opéra de Montréal, he wrote to Waters at his New York home to state his intentions. Waters wrote back and was, according to Dufour, “dismissive of the idea.” He told Dufour that in his experience, all attempts to express rock-and-roll themes in symphonic or operatic form always ended in disaster. Waters went so far as to say, “I think this is a terrible idea.”

Dufour, however, was not to be so easily denied. With a shy grin, he explains that, “For me, no never means no.” He persisted, writing a second, longer letter in which he offered his thoughts relative to Waters’s concerns.

Waters found Dufour’s subsequent missive persuasive and replied asking Dufour and his recently enlisted creative team to “do demos of a couple of pieces.”

With his newly conscripted director, Dominic Champagne, and composer, Julien Bilodeau, they immediately set to work creating demos of “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2” and “In the Flesh.” Dufour and his crew eventually took the files to Waters in New York. For Dufour and the rest of his creative team, it was essential that they meet Waters in person.

“We knew he was skeptical and we wanted to explain our artistic vision,” says Dufour. “We wanted his real feedback and for him to know we were serious.”

Waters granted Dufour and his team an interview. Several months later, he listened to the demos in his private studio.

Champagne recalls that nerves were rife. “Seven minutes can be a very long time. Waters listened to the music without moving a muscle during those seven minutes.”

More letters and phone calls followed, with Waters eventually telling Dufour on February 14, 2015, that the deal was done. The show was his.

Work began. Dufour expanded his creative crew and recruited more friends. He looked specifically for help outside the opera community, noting that he did not want creative partners “coming to the show with preconceived notions.” In fact, he notes, most of the creative principals who helped to build the show had never previously worked on an opera.

Dufour’s creative team includes Cirque De Soleil veteran, composer Julien Bilodeau; director Dominic Champagne; stage director Alain Trudel; scenic designer Suzanne Crocker; costume designer Stéphane Roy; and lighting designer Marie-Chantale Vaillancourt.

One exception to Dufour’s outsider caveat is Cincinnati Opera Director, Glen Plott, who, in 2015, visited friend and colleague Pierre Dufour in Montreal. During their visit, Dufour told Pott about his idea.

Plott was sufficiently excited that Cincinnati Opera became, in time, a co-producer. This creative marriage also resulted in Cincinnati earning the rights to the US premier as well as a ten-year worldwide partnership with Dufour.

Signing on creative partners and getting Roger Waters’s blessing was just the beginning. From concept to the first Montreal performance, it ultimately took some three and one-half years. Production costs were $3.5 million, and 174 persons were needed to bring the performance to life.

If ticket sales are any indication of public opinion, people are finding the show worth the wait. Montreal ultimately staged eleven full performances in 2015, more than doubling its anticipated initial run of five shows. Cincinnati, to date, has sold over half a million dollars in tickets with many sales outstanding.

Opera and rock fans alike should not expect a reproduction of either the album or the movie.

Dufour notes that many people offered suggestions concerning the opera’s creation. He says such input was greatly apreciated given that the production was sui generis—singular and without precedent. “We had no parameters in creating this show,” says Dufour.

And while there was a diversity of thought as to how to go forward, Dufour states that all principal parties were adamant that Another Brick in the Wall was to be conceived as an authentic opera.

In similar fashion, converting Waters’s lyrics into a compelling and artistically profound libretto was also paramount.

“I am,” Dufour says, “one who always puts the lyrics before the music.” Bilodeau, as composer, has also been careful to honor traditional operatic conventions while offering homage to Waters’s music.

Dufour, when asked if his vision had survived the collaborative process, answers with an emphatic yes, saying that while he absolutely had visions that he wished to survive the creative process, he knows his job is to be “the captain of the ship or the lunatic on the grass, if you will. It is my duty to put together a great creative team.”

Expounding, he states that in creating a production such as Another Brick in the Wall, one has no choice but to hire people one can trust and to let them do their work.

In the end, it’s always about the audience.

“This show is not a tribute to Mr. Waters, but rather, we found his piece to be so relevant that we felt it should be made into an opera. We are not working for ourselves; we are working for the audience. Of the several hundred shows I have done, whether in opera or theater, I’ve always had the same goal—to create a dialogue with the audience.”

Things are happening, being discussed regarding the future of the show. France, Argentina, perhaps another city in Canada. The future, Dufour says, will take care of itself. For now, he is happy to watch the present, which is, “like a dream, like jumping out of a plane without a parachute.”

“My main leitmotif, if this doesn’t work out, is, I’ll do something. I won’t die. I just didn’t want to regret not taking this chance. My mantra over the last four years is ‘one brick at a time.’”

–

Originally created for and published by PollyMagazine.com